This article is dedicated to a former patient of mine. He described himself in our initial meeting as “acerbic, sardonic, sarcastic and irreverent. Can you handle that?” I think he would have liked this article. But if you can’t handle it, maybe stop here.

This article was also originally published in 2020 at HealthyDebate. If anyone is to blame for my frequent posts re: Palliative Care, it’s Jack Romanelli at HD.

Like most of you, I like to laugh.

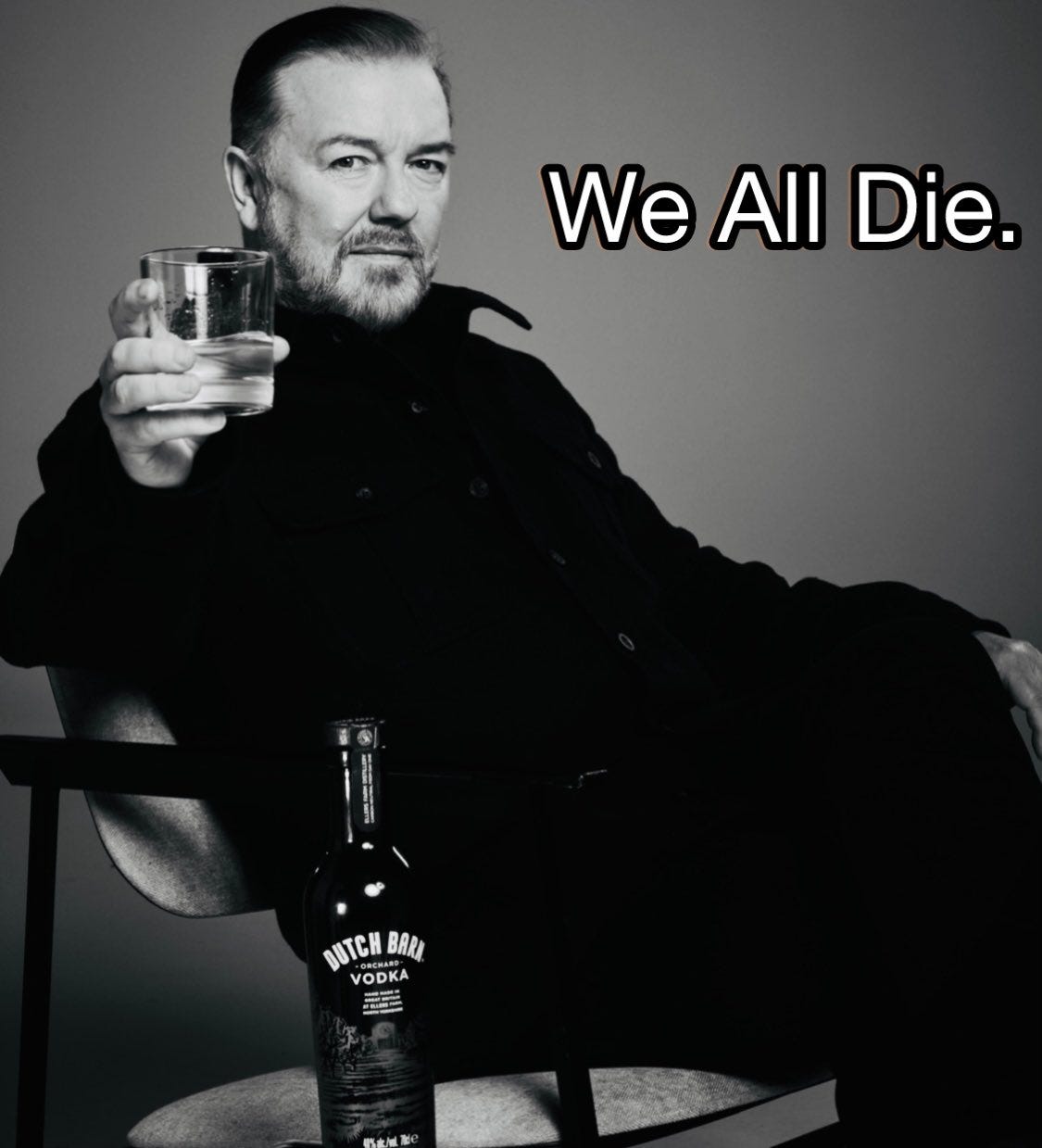

As far as comedians go, I am particularly fond of Ricky Gervais.

Ricky Gervais created and starred in “The Office,” which premiered on the BBC in 2001 before coming to North America, starring Steve Carrell, and ran from 2005-2013.

Gervais’ comedy specials are particularly hilarious and leave no stone unturned. He targets anyone and everyone. I am particularly fond of his Netflix specials: Humanity and SuperNature. I am very much looking forward to his next special: Armageddon.

And his savage takedown of the Hollywood Illuminati at the 2020 Golden Globes is the stuff of legends.

His humour is irreverent, but always relevant.

So what, you are asking, does this have to do with palliative care?

For decades, we have known about the benefits of palliative care. First, we learned that when a palliative approach is provided to patients earlier, they live longer. Then, we learned it improved quality of life for patients facing a life limiting illness. Then we learned it actually saves the healthcare system money and resources that can be reinvested back into other areas of the system. And most recently, a study in Ontario showed how palliative care can reduce ER visits, hospital and ICU admissions in patients with noncancer diagnoses (BMJ, 2020). Like our prime minister, we just keep on learning.

Atul Gawande once wrote: “If palliative care was a drug, we would patent it.” So why are patients not demanding better access to palliative care and why is health care not shoveling money into one of the few areas of medicine that actually simultaneously gives better care AND a return on investment (ROI)?

The answer is: palliative care has a public relations issue.

Now most of you in the field will immediately chime in and say “Oh yeah, we are dealing with that. We keep telling people that palliative care is not just about dying.”

So, uh, how’s that working out?

The stats in Canada are not so good – please see my article in the Medical Post on the federal government’s current (lack of) Action Plan.

The stats are also not good in Ontario, according to Health Quality Ontario’s 2019 report (HQO).

Clearly, this particular messaging is not resonating well with either the public or policymakers. Since Senator Sharon Carstairs identified access to palliative care as an issue in her 2010 report “Raising the Bar,” we have lost a decade of actually moving forward and improving access. Countless thousands of patients have died without access to high quality palliative care. Unfortunately, you probably know some of these patients.

So, what can we learn from Ricky Gervais?

People like to laugh, even the dying ones. Some of the best and funniest patient encounters I have ever had have been with patients facing imminent death. Flowing tears, bellyaching laughter. Rather than dwell on the inevitable, they choose to look on “bright side of life” (whistle if you wish here).

So, you can imagine how I felt when Healthy Debate printed my article on hospice funding in Ontario and used the notorious “sad hands” to illustrate the article that have become synonymous with palliative care (ed. note: sorry about that, big guy). Frankly, I can’t think of a more depressing way to promote palliative care, can you? It’s no wonder no one wants to discuss goals of care or advance care planning. You would need an antidepressant just to get through it.

How do we fix palliative care’s PR problem? We may already have the answer, sitting right under our noses.

Dr. Denise Marshall, from McMaster University, once proposed a “public health approach” to palliative care based on her experiences in Ireland. One example was funny beer coasters placed strategically in pubs to encourage patrons to have advanced care planning discussions. Love them or hate them, at least people talked about them.

If we can teach people to wear seat belts and condoms (separately, together is not recommended), why can’t we teach them about advance care planning and the benefits of palliative care? And given how quiet things have been with public health in recent years, I am sure they are looking for some work to justify their existence.

Here’s another example. Check out how New Zealand teaches parents to talk to their kids about Internet pornography.

Why don’t we consider messaging like this video about insurance on “dumb ways to die.”

So maybe, we need a similar approach here in Canada when it comes to palliative care?

Imagine this: instead of constantly nagging people that palliative care is “not just about dying,” why not have some fun with it?

Imagine if Marvel’s Deadpool, Canada’s very own R-Rated Marvel superhero (played by Vancouver’s Ryan Reynolds), decided to do public service announcements about palliative care? Clearly the irony of someone who can’t die teaching us about dying is simply too delicious to ignore. If only Ryan would put down the Aviation gin, put Mint Mobile on hold and leave poor Hugh Jackman alone.

And for those who still won’t embrace the “death and dying” approach, I give you Monty Python. During a global pandemic, well, that just writes itself:

Palliative care started in the 1960s with Dame Cicely Saunders in St. Christopher’s Hospice in England. It began when she decided that dying patients deserve the same high-quality care other patients enjoy. Palliative care gets its name from Dr. Balfour Mount, a urologist (pun intended) who created Canada’s first palliative care unit in Montreal (in your face, Manitoba). Despite numerous attempts over the years to distance itself from death and dying, palliative care continues to be associated with the grimmest of reapers.

So, I submit to you, constant readers, that rather than run screaming away from its association with death and dying, I am suggesting that palliative care “lean into the curve.” Clearly what we are doing is not working. All the data and studies show that access to palliative care remains suboptimal. We simply cannot continue to ignore the clear benefits to patients, families and the greater healthcare system.

The time has come to try a different approach.

I mean, we can continue to bang our heads against the wall but the National Football League has clearly shown us what that will accomplish (CTE, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, for the non-medical readers). Einstein has thoughts on our current approach too.

Even if you hate this idea, you just proved my point by reading and responding to this (that’s why there is a comments section below). We need to get people talking. As Christopher Walken reminds us, “we need more cowbell.” I say we oblige him.

(I’ll be super disappointed if nobody gets this Easter egg in the comment section).

So just like Kathy Kortes-Miller’s book tells us that “Talking about death won’t kill you,” neither will palliative care shrivel up and melt away if it finally admits that death and dying are part of the plan. And maybe we can have some fun while we are at it.

Let’s be serious for a moment. If caring for patients at the end of life has taught me anything, it is the bravery and grace they model for the rest of us. The vast majority of patients want to talk about death and dying, they just need to know we are open to having these discussions and that we will be there with them through the good times and the inevitable bad times too. Is that too much to ask?

It is often said we live in a “death-fearing society.” If we, meaning the palliative care community, can’t talk about death and dying, then who can?

In some ways huge amounts of what we do in primary care is a weird side eye version of palliative care. Palliative care is care provided with a view to relieve symptoms with no curative intent. Last time I checked in the family practice office we don’t actually cure a hell of a lot of stuff. We rarely cure diabetes (ozempic and similar meds may change that but still only while taking them), arthritis that isn’t in a joint that can be rebuilt (your aching hands, feet, ankles, shoulders and elbows (at least most shoulder and elbow stuff with some newer caveats), the list goes on of chronic conditions that we can’t cure. Yes, most aren’t immediately life threatening which is an important difference but honestly in medicine, outside of infectious disease and surgical care, there are precious few conditions we cure. But patients think we cure everything, “You mean I can’t stop taking my Diabetes or HTN drugs?” Medicine as a whole needs a reality check. We can make you feel a lot better for a lot of things but we likely can’t cure many of them. Maybe we need to get this first principle truth across and then expand it to the more traditional life limiting illnesses. But then everyone would lose faith in medicine. Which is a challenge in its own right.

"I got a fever... and the only prescription... is more cowbell!" Thank you for the many chuckles and iconic references in this article. If my psychiatry textbooks taught me anything, it is that good humor is a very mature response to conflict, so I try to incorporate it whenever I feel it will be well-received.

My grandmother apparently shares that sentiment: Her 99th birthday is coming up next month, so my cousin told her "Just one more year, Ouma, then you get to raise your bat." (To those not familiar with cricket, the saying refers to the fact that the batsman would often raise their bat in celebration of reaching a century.) My grandmother did not waste a breath before answering in her deadpan, no-nonsense way: "And then you must take that bat from me... and whack me over the head with it!"

Looking forward to reading more of your writing :)

Warm regards from South Africa

Dr Tania de Vos (an aspiring oncologist with a love for palliative medicine and the people that care)